What students expect from their exchange student experience may vary, from traveling to making friends of various backgrounds, mine was studying (yes, I am that nerdy Asian in your class). I'm a senior back in my home university, and I have been feeling stuck in a rut for a while, confused about my feelings towards studying. I thought I liked studying, but where has all my passion gone? Was it just an illusion? I wanted my semester studying at Temple to be an opportunity to regain confidence and passion for studying and so far, it seems like a success. Unlike many lecture-driven courses in my home university, Temple’s require active student participation and (as arduous as they may be) fun, creative assignments like holding an interview or an exhibition even.

"Race and Diversity in Children and Young Adult Books: Reading Between the Lines” is one of my favorite courses I'm taking this semester. In the course, students read a young adult fiction featuring children of various racial identities every other week and discuss their thoughts about it. What I like most about this course is the thought-provoking questions the professor casts on us. Given the topic of the course, most of them are about reflecting on our (racial) identities in the US context - "Who are you?", "What is your identity", "How would you describe your racial/ethnic identity?" and "How is your identity changing?". Of all these interesting questions, the one that lingered in my mind was "Where does your name come from?". I have never thought of this in my life, but now I solemnly think about the origin of my name here in the US, where Minha gets a red line under it and James and Ellen and Joe don't when you type them in an iPhone.

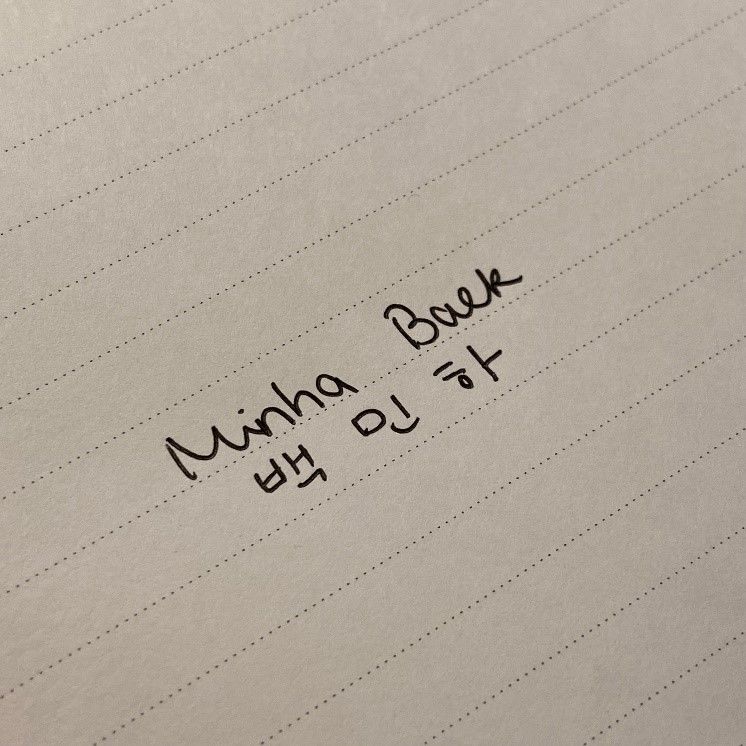

My name "Minha Baek", or to put it in the Korean way, "Baek Minha", was given by my grandparents. In Korea, naming is a very serious business - there are even professional "namers" who give names to people. We believe that names bound you to a certain destiny - many get their names from these namers even later in their lives and change their name to change their "destiny". My grandparents got my name from one of the professional namers, too, with love and care.

For your information, Korea has a unique alphabet set created by King Sejong, but before that, people have long used Chinese characters, or "Hanja" (meaning Chinese character in Korean), to write Korean words. My first name is also composed of two Hanja words. As each Chinese character is composed of meaning and pronunciation, "Min" means jade and "Ha" means under. So, like, I'm a person who's under a jade? Not necessarily, because two characters are not really picked to make sense (but of course overall meaning should be good, too), but rather carefully selected under "name-ology" principles. I am not an expert, but it has to do with how many strokes you need to write each character. "Min" follows a certain naming convention in Korea as well, which is using a common sound when naming siblings. Two of my sisters all have first names starting with "Min".

My name has a long, interesting story, but it's only interesting because I'm in the US as an Asian. If I tell this story to friends in my country, they will go, "So what? That's nothing special". My name will never stand out in Korea either; everyone has three (or sometimes two or four)-syllable-names like me. However, in the US, I get nervous every time a professor takes attendance or someone asks for my name. My name marks me as different, and not knowing what information and past experiences others would recall when seeing my Asian name makes me nervous and scared, even. Not to mention the frustrating process of correcting the spelling and pronunciation of my name to the others. I've gotten Mil-ha, Ming-ha, and even Tina.

That is probably why many Korean exchange students have their "English names". Usually, it is not something as dramatic as Minha becoming a Jessica, but rather changing your name into a more Americanized one to make it easier for the others to pronounce. It's like Jinha becoming a Jen, and Jihye becoming a Jay. Because of this dual-name situation, I have experienced American students not knowing who I am referring to when I use Korean names to refer to other Korean students. It's a small confusion that happens when you use two names to introduce yourself.

Yet, I don't think that it is disgraceful to have an English name. Rather, it seems like more of a light-hearted and fun experiment of your identity. It even seems adventurous to explore your "American" identity in a new environment. On the other hand, there would be some people who choose to have American names for more practical and political reasons. Some studies have shown that white-male-sounding names get more job offerings on LinkedIin and papers under racial-minority-sounding names get less recognition in academia. I'm not currently looking for any job or in academia, but I suddenly get nervous putting my Korean name on Tinder. Oh well.

A children's book I read for the "Race and Diversity" class called "The Name Jar" by Yangsook Choi captures this frustrating experience caused by having a non-American name from a Korean child's perspective. The protagonist Unhei is a Korean child who has just come to the US. When she introduces herself to American kids on a school bus, they make fun of her name. Suddenly self-aware of her name, she makes a "name jar" to get ideas for her English name, but eventually, she gathers up the courage to introduce her real name to the whole class, even with her handwriting in Korean.

Like Unhei from the book, I also use my Korean name here in the US. Minha is Minha, even when I'm in America. I didn't change my name so that I could enjoy the glory to be the first Korean name to an American who has never seen any Korean person in their life. Not. It sounds glorious, but to be frank, I am a proud person who likes to put everything in meaning. Yet I'm a cowardly proud person so I didn't put a hyphen which is often used to write Korean names in English. I didn't want my already odd-sounding name to stand out by adding an extra hyphen to it.

Still, what would have been like if I chose an English name? I imagine myself living in the US with my brand-new English name. What would my English name be? Martha? Hope? Clara? June? I get a little elated, feeling like I'm choosing a codename as a spy, but soon I quit, thinking that it would feel like lying whenever I introduce myself with an English name.